In recent years, online privacy literacy has often been regarded as a potential solution to people’s seemingly paradoxical behaviors in online environments. Based on empirical findings that Internet users rarely implement privacy and data protection strategies,1 it has been suggested that they are simply not literate enough to make informed decisions in online environments. Throughout the last years, we2 have been working on reconceptualizing online privacy literacy and providing reliable and validated instruments to measure online privacy literacy objectively. In this post, I would like to summarize different projects and publications that I was involved in over the last years. I also would like to describe how they led to my latest publication called “It is more than just privacy risk awareness: A reconceptualization of online privacy literacy as a composition of knowledge, abilities, and skills”.

Online privacy literacy has often been regarded as a requirement for informational self-determination. Without the knowledge and skills necessary to navigate online environments and to ensure the protection of one’s personal information as well as to limit other’s access to the self, people cannot be autonomous in communicating and using online services. Hence, fostering online privacy literacy through education or other types of interventions has often been discussed as a potential solution to data protection issues on the Internet – both in political and scientific circles. Yet, it seemed that the the discussions remained superficial. Blinded by the potential of education to stopgap people’s seemingly paradoxical behavior, 3 people seemed all to ready to believe in an individual’s ability to learn the skills and knowledge to navigate the Internet safely and responsibly.

But I think that also the research lacked behind. First studies in recent years only started to investigate people’s privacy literacy. Their initial findings suggest that the level of literacy was rather low4 and that people often overestimate their knowledge5 A more recent study which investigated three dimensions of online privacy literacy found that higher levels in all three dimensions predicted data protection.6 Although prior work on online privacy literacy existed, we realized that no comprehensive concept of, and no validated and reliable instrument to measure online privacy literacy existed. Prior concepts were often fragmented (focusing on one particular knowledge area, e.g., knowledge about data protection law or institutional practices of data collection and usage) or were focusing on particular platforms (e.g., Facebook). Additionally, such instruments were either self-reports or random, unvalidated knowledge items. In light of this, we set out to define this concept more comprehensively.

Conceptualizing online privacy literacy as a multi-dimensional knowledge concept

So far, online privacy literacy had mostly been operationalized as a pure knowledge concept. A few studies had shown that such a privacy knowledge is related to more self-data-protection. In a first step, we conducted an exhaustive qualitative content analysis of prior literature on privacy literacy and a profound content analysis of different sources (privacy policies, juridical documents, EU deliverables…) capturing a variety of aspects relevant to online privacy. The aim was to capture any aspect or area that we deemed related to online privacy literacy. What knowledge should people have? Which skills should they possess?

In the end, we came up with four knowledge dimensions: (1) knowledge about practices of organizations, institutions and online service providers (e.g., data collection, sharing, usage, and analysis); (2) knowledge about technical aspects of online privacy and data protection (e.g., understanding concepts such as cache, cookies, and how they relate to one’s privacy); (3) knowledge about laws and legal aspects of online data protection as well as (4) knowledge about European directives on privacy and data protection, and (5) knowledge about specific strategies for individual privacy regulation (e.g., what type of password to use, how to manage up privacy setting, etc). Based on these dimensions, we defined online privacy literacy as

a combination of factual or declarative (“knowing that”) and procedural (“knowing how”) knowledge about online privacy. In terms of declarative knowledge, online privacy literacy refers to the users’ knowledge about technical aspects of online data protection and about laws and directives as well as institutional practices. In terms of procedural knowledge, online privacy literacy refers to the users’ ability to apply strategies for individual privacy regulation and data protection (p. 339).

Based on the content analysis, we then developed a first item pool that we believed captured all aspects of online privacy literacy. We summarized the findings of the content analysis in the following publication:

- Trepte, S., Teutsch, D., Masur, P. K., Eicher, C., Fischer, M., Hennhöfer, A., Lind, F. (2015). Do people know about privacy and data protection strategies? Towards the “Online Privacy Literacy Scale” (OPLIS). In. S. Gutwirth, R. Leenes & P. de Hert (Eds.). Reforming European Data Protection Law.(pp. 333-365). Springer: Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9385-8 [Link | Preprint]

Development and validation of the online privacy literacy scale (OPLIS)

In a second step, our aim was to reduce the large item pool and develop a comprehensive, yet useable scale to measure online privacy literacy. Based on the initial item pool with 113 knowledge questions, we conducted three consecutive studies with which we tested the items for overall fit with the proposed theoretical concept. We measured all five dimensions identified in the qualitative content analysis. However, the analyses have revealed that the “legal” dimensions 3 and 4 were not distinct. The final scale hence includes only four dimensions of privacy literacy and consists of 20 items (five items per dimension).

Figure 1. The estimated bifactor model (Masur, Teutsch & Trepte, 2017).

The psychometric quality of the scale was tested using structural equation modeling. The results of the studies show that the multidimensional concept of online privacy literacy can be supported with empirical data. Yet, we found that the dimensions identified in the literature do not represent distinct knowledge areas. Instead, the common variance in all items accounted for a strong global factor that represented actual online privacy literacy. Accordingly, we suggested to model online privacy literacy as a bifactor model which accounts for both the global variance and domain specific variances.7

The model was validated with a quota sample of German internet users (N = 1.932). Based on different criteria the scale’s quality can be regarded as good. Specifically the global factor predicted different types of data protection behavior. The results of the three consecutive studies were published the the journal “Diagnostica”:

- Masur, P. K., Teutsch, D. & Trepte, S. (2017). Entwicklung und Validierung der Online-Privatheitskompetenzskala (OPLIS) [engl. Development and validation of the online privacy literacy scale]. Diagnostica, 63, 256-268. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924/a000179 [Link | Preprint]

To make the scale available to the public, we also set up a website that features not only all items of the scale, but also instructions and tutorials on how to use them in different scenarios and norm tables for comparing individual results with the German population:

A normative perspective on privacy literacy and “do it yourself”-data protection

Since its publication, the scale has been used in several studies – both nationally and internationally. Although higher literacy seemed promising in predicting people’s engagement in data and privacy protection, we started to question in how far fostering online privacy literacy was the right way to tackle the challenges of online privacy. In a chapter that was published as proceedings of the CPDP (a large conference on computers, privacy and data protrection), Tobias Matzner, Carsten Ochs, Thilo von Pape and I dove more deeply into the question of whether individual citizens should be responsible for their own data protection. Again, do-it-yourself (DIY) data protection has often been considered as an important part of comprehensive data protection. Fostering DIY privacy protection and providing the respective tools was seen both as important policy aim and as a developing market. Individuals are meant to be empowered in a world where an increasing amount of actors is interested in their data. The results of our scale development paper somewhat seemed to support this claim.

We took a step back and analyzed the preconditions of this view empirically and normatively: Thus, we asked first: Can individuals protect data efficiently? And second, should individuals be responsible for data protection. We found that individuals barely engage in sophisticated data protection that would allow them to restrict access of companies or institutions to their data and further argue that for normative reasons, a wider social perspective on data protection is required. Failing to see the larger, structural reasons behind individual lacks in privacy protection, does not attribute responsibility to the government as the actor who might actually be able to address structural problems. Seeing online privacy literacy as the solution thereby removes the responsibility of the government to ensure its citizens’ self-determination. The chapter has been published here:

- Matzner, T., Masur, P. K., Ochs, C. & von Pape, T. (2015). Self-Data-Protection – Empowerment or burden? In: S. Gutwirth, R. Leenes & P. de Hert (Eds.). Data Protection on the Move. (pp. 277-305). Springer: Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-7376-8_11 [Preprint]

The role of online privacy literacy in democratic societies

In light of this, we started to question the role of online privacy literacy. By investigating the more recent literature on interventions and potential outcomes, we found that often enough, increasing people’s knowledge (even in all areas that were captured by OPLIS) did not necessarily result in a behavior change (e.g., less self-disclosure). It seemed even possible that people gained more knowledge through using certain privacy protection strategies and not vice-versa.

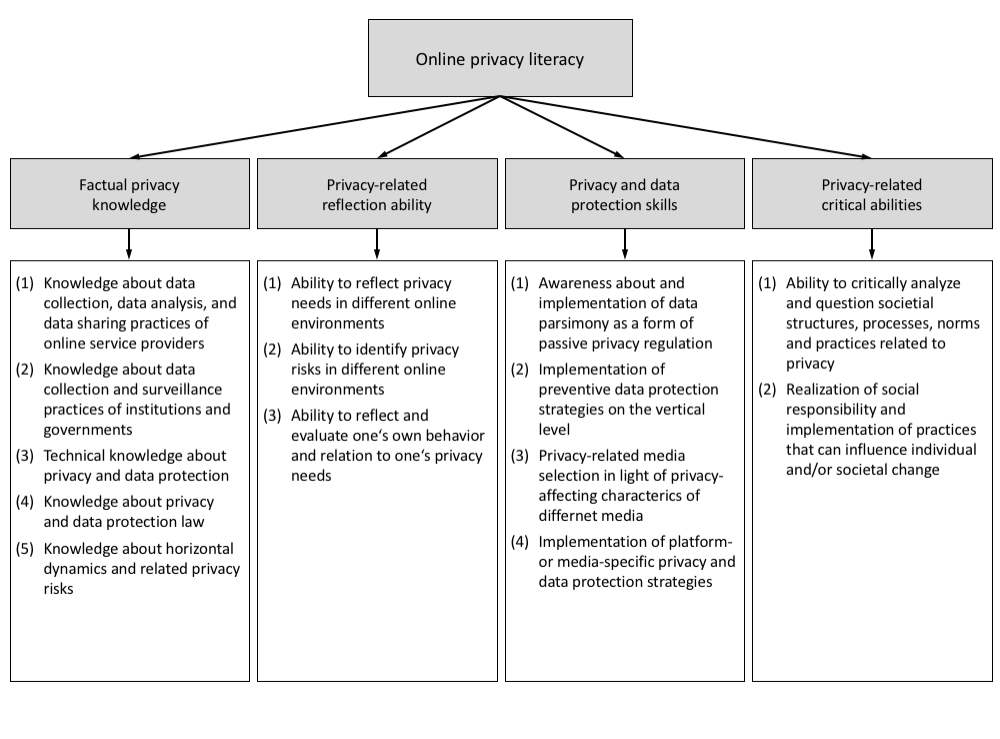

It was hence unclear whether a respective intervention actually contributes to more self-determination on the Internet and whether it makes people behave more deliberate and more in accordance with their privacy needs. Through continued discussions and reviews of the literature, we came to the conclusions that online privacy literacy should be conceptualized as a combination of knowledge and specific abilities and skills. For this purpose, a reconceptualization is proposed that includes privacy-related reflection and critical abilities as well as practical privacy and data protection skills next to factorial knowledge about economic, technical, and legal aspects of online privacy.

We argued that in order to be a true enabler for self-determination (including political responsibility), privacy literacy has to be viewed as a more complex set of skills, abilities and knowledge sets. The first installment of this model was published in the following paper:

- Masur, P. K., Teutsch, D., Dienlin, T. & Trepte, S. (2017). Online-Privatheitskompetenz und deren Bedeutung für demokratische Gesellschaften [engl. Online privacy literacy and its significance for democratic societies]. Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen, 30 (2), 180-189. https://doi.org/10.1515/fjsb-2017-0039 [Link]

A reconceptualization of online privacy literacy

In my most recent publication, I developed this idea further and proposed a comprehensive model of online privacy literacy that outlines several factual privacy knowledge areas, privacy-related reflection abilities, privacy and data protection skills, and privacy-related critical thinking abilities (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: A comprehensive framework of online privacy literacy (Figure taken and translated from Masur, 2018).

With this model, I aim to provide a novel perspective on how to conceptualize privacy literacy. I agree that one of challenges today is that user are not literate enough to navigate online environments in a self-determined manner. But in contrast to prior literature, I do not think that is only a lack of knowledge that prevents them from becoming critical media users. Instead, I suggest that they (1) lack the knowledge to identify the risks involved in using online media, (2) do not have the necessary self-reflection abilities to questions and reflect their own behavior, (3) do not have the procedural skills to implemented increasingly more sophisticated privacy protection measures, and (4) lack the critical thinking ability to criticize the status quo and realize their own potential in actively changing their social and structural environments.

I argue that only by acknowledging reflection and critical thinking abilities, online privacy literacy may enable true self-determination. Particularly, individuals need to become critical in that they develop the ability to critically question and criticize institutional practices, the lack of usable data protection tools, and thereupon decide to change this status quote (e.g., by causing societal change through a certain voting behavior).8

With this paper, I am drawing from classical media literacy theory to arrive at a more comprehensive definition of what a literate Internet users and particularly a privacy literate user may look like. The theoretical paper was published in the German journal “Medien & Kommunikationswissenschaft”:

- Masur, P. K. (2018). Mehr als Bewusstsein für Privatheitsrisiken: Eine Rekonzeptualisierung der Online-Privatheitskompetenz als Kombination aus Wissen, Fähig- und Fertigkeiten [engl. It is more than just privacy risk awareness. A reconceptualization of online privacy literacy as a composition of knowledge, abilities, and skills]. Medien & Kommunikationswissenschaft, 66(4), 446 – 465. https://doi.org/10.5771/1615-634X-2018-4-446 [Link]

Conclusion and future perspectives

It has been questioned before why we need online privacy literacy a distinct concept – particularly as it (and even more so my latest conceptualization) is so close to classical media literacy concept. In the paper, I answered the following (translated from German):

Despite overlaps with some dimensions of media and digital literacy, I argue that the independent consideration of online privacy literacy makes sense both from a theoretical and an empirical point of view. Firstly, the focus on privacy-related knowledge dimensions, abilities and skills allows to explicit address necessary prerequisites for informationally self-determined behavior in online environments. Such a concept of literacy makes it possible to investigate particularly those person characteristics that actually allow the individual to determine for himself how his personal information and data is collected and used by potential third parties. Secondly, the concept allows for a conceptual condensation that is absolutely necessary for empirical assessments and imperative for potential educational programs designed to prevent irrational handling of one’s own privacy in online environments. Only the clear focus on privacy allows for reasonable operationalizations that are directly related to privacy-related behavior.

With this in mind, I believe that investigating online privacy literacy as well as its antecedents and consequences is an important goal. At this moment, several international project use OPLIS to investigate online privacy literacy in different cultures and contexts. Given that privacy must often be understood form a situational 9 (or at least a contextual perspective10 such studies are of utmost importance to understand the circumstances under which Internet users make use of their knowledge and skills and under which they don’t.

I will continue this research program in the next years aiming at understanding the connection between media and privacy literacy (is it a distinct concept or rather a subdimensions of a modern concept of media literacy?) and develop approaches toward assessing the various dimensions that I outlined in the latest paper. It is my hope that this research inspires other privacy scholars but also provides some valuable insights for practitioners and policy makers.

Footnotes

- Matzner, T., Masur, P. K., Ochs, C. & von Pape, T. (2015). Self-Data-Protection – Empowerment or burden? In: S. Gutwirth, R. Leenes & P. de Hert (Eds.). Data Protection on the Move. (pp. 277-305). Springer: Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-7376-8_11 [PDF]

- The research program was started by Sabine Trepte, Doris Teutsch and me. Throughout the years, I further worked on this project with other scholars such as Tobias Matzner, Thilo von Pape, Carsten Ochs, Carolin Eicher, Mona Fischer, Alisa Hennhöfer, and Fabienne Lind who all contributed immensely to my current understanding of online privacy literacy.

- Since 2005, empirical work on people’s disclosure behavior in online environments (particularly social media such as Facebook) often found that people disclose a large amount of information despite strong privacy concerns. This observation has been termed the “privacy paradox”. Yet, more recent studies with larger samples and more sophisticated methods as well as meta-analyses have shown that concerns do relate to privacy behavior suggesting that people’s online behavior is not as paradoxical as it seems.

- Hoofnagle, C. J., King, J., Li, S. & Turow, J. (2010). How different are young adults from older adults when it comes to information privacy attitudes and policies? Retrieved October 7, 2016, from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/SSRN_ID1589864_code364326.pdf?abstractid=1589864&mirid=1

- e.g., Morrison, B. (2013). Do we know what we think we know? An exploration of online social network users’ privacy literacy. Workplace Review, April 2013 Issue, 58–79. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.1.4898.0567

- Park, Y. J. (2013). Digital literacy and privacy behavior online. Communication Research, 40, 215–236.

- Reise, S. P. (2012). The Rediscovery of bifactor measurement models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 47, 667–696; Reise, S. P., Moore, T. M. & Haviland, M. G. (2010). Bifactor models and rotations: Exploring the extent to which multidimensional data yield univocal scale scores. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92, 544–559. doi:10.1080/00223891.2010.496477

- The recent demonstrations against the new European copyright directive is an interesting example of such an critical thinking ability

- See e.g., this post.

- Nissenbaum, H. F. (2010). Privacy in context: Technology, policy, and the integrity of social life. Stanford: Stanford Law Books.

Pingback: New Publication: Can online privacy literacy support informational self-determination? – Philipp K. Masur